Issue 4 | Fall 2021

Can You See Me Now?

Fashion to subvert mass surveillance, and fashion to encourage it, too.

Text: Christian N. Kerr

Art: Karen Nicole

Bill Cunningham, the late New York City photographer famous for both his blue chore coat and his candid images of regular city-denizens, described fashion as “the armor to survive the reality of everyday life.” These days, reality is mediated through computer vision, analyzed by increasingly authoritarian algorithms.

We now get dressed before a double-sided mirror and walk beneath a fine mesh of surveillance that blankets New York City. The Domain Awareness System, built by Microsoft for the NYPD, trains a network of twenty-thousand CCTV cameras, countless chemical, radiological and biometric sensors, and multiple behavioral analytics software to monitor our every move.

Faces can be run through a recognition algorithm like Clearview AI’s, which looks at over three billion photos scraped from social media sites like Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube to achieve alarmingly accurate identifications. It’s so powerful it can find faces in even the background of images.

“It’s a complete transformation of the city,” says Albert Fox Cahn, founder of the privacy advocacy group Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (STOP), “from a place which was once so sprawling that its sheer size guaranteed anonymity, to a place where every decision we make in public is scrutinized, surveilled, and potentially flagged as a threat.”

Can fashion still be an “armor” for a reality so thoroughly monitored? Luckily, a wardrobe of options is out there for the anti-surveillance sartorialist.

Reflectacles’ Ghost glasses, designed by Scott Urban, extend the wearer a sort of Clark Kent camouflage. When worn, they render key features of your identity essentially hidden to digital eyes. They feature special frames that flare into an obfuscating orb when hit with a camera’s flash. Infrared-blocking lenses appear as blank spaces when seen through iris scanning and facial mapping systems.

For a more ostentatious evasion, consider Adam Harvey’s CV Dazzle concept, which uses avant-garde hairstyling and makeup designs to confound the ways in which facial recognition algorithms function. Slants of bangs over the brow and ears, streaks of color across the cheeks and lips, and constellations of glittery studs can be combined to make you indiscernible to certain systems.

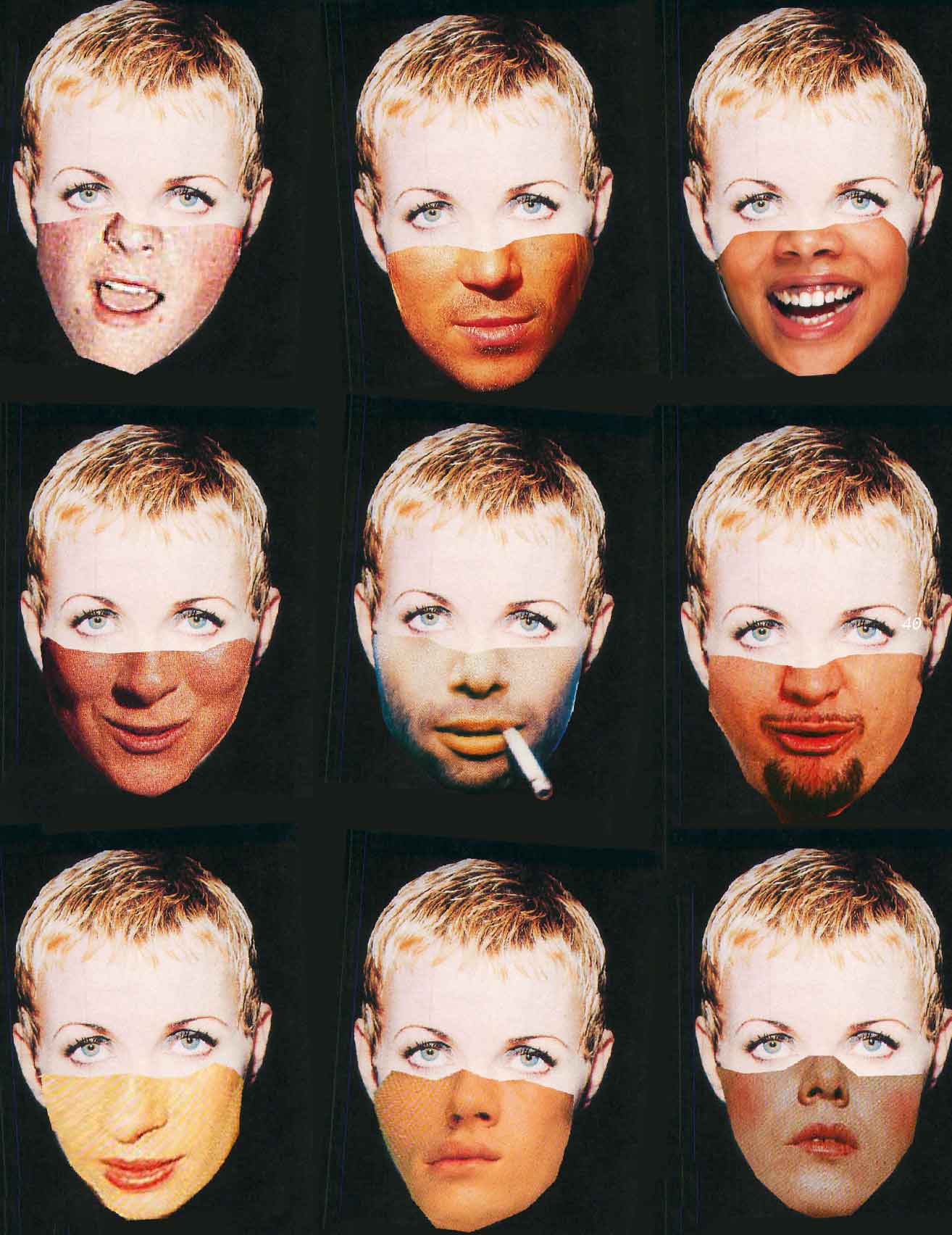

Simone C. Niquille’s “REALFACE Glamouflage” T-shirt, designed in 2013, features twisted visages of impersonators that might be tagged as Michael Jackson or Barack Obama by a facial recognition program. “Privacy through piracy,” she calls it. Glamouflage’s utility is conceptual, more meant to spark conversation on identity ownership and image rights than act as some sort of invisibility cloak.

“I was and am much more interested in awareness and behavior,” she says. “Rather than using design to offer a solution that would end in an endless cycle of updating said solution in accordance with technology.”

There is a fundamental flaw in all of these designs. What works today isn’t likely to work tomorrow, and what works against one system isn’t guaranteed to work against another.

Hundreds of different systems, from Facebook’s DeepFace, and Google’s FaceNet, to Amazon’s Rekognition, and startups like SenseTime and AnyVision, are trying to outdo each other’s ability to see you for who you really are, no matter what you’re wearing.

These companies scrambled to adapt to the sudden ubiquity of face masks as the coronavirus spread, incorporating thermal imaging and predictive profiling to try and peer beneath what’s covered.

Even a mask from Maskalike, printed with a computer-generated face from Thispersondoesnotexist.com, won’t mystify recognition algorithms for much longer. SenseTime already boasts a mask erasure update they call, “highly effective.”

Consider the Adversarial T-shirt, developed by researchers at Northeastern University with the support of IBM’s Watson AI Lab. The shirts appear as something like a pixelated Seurat painting to the naked eye and nothing at all to the YOLOv2 object-detecting algorithm it was designed to thwart.

The Adversarial T-shirt uses a novel modeling tool to create a design that remains undetectable even when wrinkled.

“This base work,” says Dr. Xue Lin, one of the researchers at Northeastern, “will provide insight to people when they design their deep learning or computer vision systems. So when we know there could be a possible problem, we can based on that, design more robust systems.”

What’s puzzling to an algorithm at first becomes just another piece in its advancement. The endgame is a system so sophisticated it can index everything it sees and even identifies emotion with perfect accuracy. In order to reach this stage, technology companies need not only the acquiescence of the public but its active engagement. Enter the “Metaverse,” where our physical reality is collapsed into the virtual. In exchange, we’re presented with an individualized reality, customizable to our settings and mediated through the application of our choosing. The more we submit, the deeper their data pool, and the more immersive a metaverse they can sell us. “What we should realize,” says Scott Urban, the maker of Reflectacles, “is that we as people have become and participate in the Surveillance State, and willingly so.”

There’s no shortage of exciting applications to encourage this transition:

So-called smart glasses like Facebook’s RayBan Stories and Snapchat’s Spectacles make it alarmingly easy to upload audio and video recordings to their respective apps, regardless of whether the documented party has consented; while Google Glass’s augmented reality adds the ability to overlay information from the Internet in real-time across its screen/your perspective.

Facebook’s Spark AR and other photo and video filter applications encourage the creation and use of augmented reality effects that can match you to your doppelganger in a famous painting or make it appear like you’re engulfed in flames or encrusted in ice.

Cosmetics retailers like Sephora and MAC have installed virtual try-on kiosks that let you test their products without having to touch anything; online marketplaces like Etsy and Amazon allow you to see how their product will look in your home before you click “Buy.”

These AR applications cut down on waste and returns, but they also siphon off our biometric and spatial data with dubious intent.

For a full ingress into the virtual, there are infinite avatars and upgrades for sale to embody your persona across the metaverse. Genies is the exclusive avatar provider for Warner Media Group artists like Justin Bieber, Rihanna, Migos, and Shawn Mendes.

The company their characters as, “the fantasy version of you.” But in their promise of boundless expressiveness belies a paradox: the blockchain necessary to ensure the exclusivity and authenticity of these digital tokens inextricably links these digital tokens to your physical being.

Whereas the Internet, at least in theory, once offered an escape from the singular self, the metaverse conscripts these possibilities.

“Each of us makes a choice to adapt to all the new technologies that are thrown at us,” says Urban. “Whether they be on your phone, in your car, or in your head, we all have this small option to say ‘I agree’ or ‘I prefer not to’.”

But, thanks to billions in capital, it’s getting harder and harder to opt-out of these terms of surveillance.

Eventually, as every space gets devoured by the all-seeing eyes of the technopolis, our agreement will be implicit in our very existence.

Adam Harvey, the creator of CV Dazzle, is concerned about the implications this has on our individual liberty.

“It elevates the user to a micro-authoritarian, giving them the power to impose their reality on others,” he wrote over email. “In doing so, the author of an augmented reality overwrites and erases the actual reality of another, denying them their right to self-determination.”

Fox Cahn echoes Harvey’s fear, foreseeing “the dehumanizing distance that has defined drone warfare becoming a part of in-person human interaction.”

“It is a systemic issue and not one for design solutionism,” says Niquille. She urges researchers to move “away from products towards investigating datasets, models and the processes behind the technology.”

Her latest work, a short film called Elephant Juice (a mishearing of “I love you”), shows a prospective job candidate training their face before a mirror in preparation for a fully automated webcam interview, exposing the limitations of machine learning’s capacity to comprehend the nuances of human emotion.

As another example, she cites Harvey’s Exposing.ai project, which provides a search engine to see if your Flickr photos were harvested for any AI surveillance research projects. Bad news if you find out they were, though. Once your biometrics are scraped, there’s no getting them back.

Fox Cahn, whose organization, STOP, partnered with Harvey to make Exposing.ai publicly available, wants to weed out the problem by the root.

“This technology is currently broken and error-prone,” he says, “and then when you do fix those problems you end up with the perfect tool of authoritarian control.”

The only answer, as he sees it, is to ban facial detection and recognition software completely, which can only happen with a mass mobilization against the convenience and security such technologies supposedly proffer.

Until then, the only option might be saying “no.”

This story appears in the new issue of Secret, available now.